Tug Hill Snow Pack Saturation

Watertown sits in the shadow of the Tug Hill Plateau. It receives massive lake-effect snow loads. This creates a "wet blanket" effect. The snow insulates the base of the monument but melts against the stone face. The granite absorbs this meltwater continuously for months.

When the temperature drops to -20°F, that trapped liquid freezes. It expands 9% instantly. This generates internal pressure exceeding 2,500 PSI. The rock cannot stretch. It fractures. The surface shears off in sharp, jagged flakes (spalling).

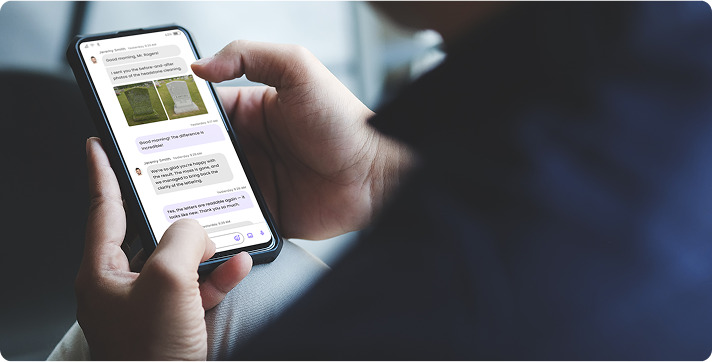

Searching for headstone cleaning services near me often leads to pressure washing ads. In Jefferson County, this is destructive. High-pressure water forces more liquid past the stone's natural defense. If a freeze follows, the stone explodes from the inside. We use specialized grave site cleaning services. We utilize low-pressure chemical rinsing and hydrophobic sealers. We keep water out of the pores.

Black River Limestone Dissolution

The local geology is the Black River Group (limestone). Many historic markers in Brookside Cemetery are carved from this local stone. It is calcium carbonate. It is chemically vulnerable to acid rain.

Precipitation is naturally acidic. It dissolves the calcium binder holding the stone together. The surface becomes "sugary" (granular disintegration). Inscriptions lose their edges. Pressure washing blasts this weakened surface away. We use consolidation treatments. These liquids soak into the stone and re-harden the matrix, replacing the lost binder.

"Paper City" Sulfite Crusts

Watertown was the "Paper City." Mills lined the Black River for a century. They burned coal and used sulfite processes. This exhaust settled on the cemeteries. It bonded with the stone.

On marble, this pollution triggers a chemical reaction. Sulfur mixes with rain. It converts the calcium surface into a black gypsum crust. This is not dirt. It is dead stone holding carbon soot. Scrubbing this crust destroys the inscription details. We use ammonium carbonate poultices. These pastes dissolve the chemical bond. We rinse the black scab away without abrasion.

Deep Frost Heave

The frost line here goes deep. The ground is Glacial Till. It is a dense matrix of clay and stone. It acts like a sponge. It holds water.

When this water freezes, it forms an "ice lens." This lens expands upward with hydraulic force. It lifts the monument foundation. In spring, the lens melts. The soil loses cohesion. The foundation drops back down. It never lands flat. The monument tilts. Adding topsoil is a cosmetic waste; the physics of the soil have not changed. For permanent tombstone repair and restoration, we stabilize the sub-grade. We excavate below the frost line. We install a friction pile of angular gravel. This drains the water. It stops the heave.

Ferrous Pin Failure ("Rust Jacking")

Historic monuments here often use iron pins to connect the base and the die. Snow melt penetrates the joint compound. The iron rusts. Rust takes up 600% more space than steel.

This expansion pushes outward with massive force. It acts like a wedge splitting the stone block. Rust stains on the base are the first warning. We disassemble the monument. We drill out the corroded iron. We replace it with stainless steel or epoxy dowels. This eliminates the stress point.